Not long ago Dr. Gattegno taught a demonstration class at Lesley-Ellis School. I don't believe I will ever forget it. It was one of the most extraordinary and moving spectacles I have seen in all my life. The subjects chosen for this particular demonstration were a group of severely retarded children. There were about five or six fourteen- or fifteen- year-olds. Some of them, except for unusually expressionless faces, looked quite normal; the one who caught my eye was a boy at the end of the table. He was tall, pale, with black hair. I have rarely seen on a human face suchanxiety and tension as showed on his. He kept darting looks around the room like a bird, as if enemies might come from any quarter left unguarded for more than a second. His tongue worked continuously in his mouth, bulging out first one cheek and then the other. Under the table, he scratched--or rather clawed--at his leg with one hand. He was a terrifying and pitiful sight to see.

With no formalities or preliminaries, no icebreaking or jollying up, Gattegno went to work. It will help you see more vividly what was going on if, providing you have rods at hand, you actually do the operations I will describe. First he took two blue (9) rods [1] and between them put a dark green (6), so that between the two blue rods and above the dark green there was an empty space 3 cm long. He said to the group, "Make one like this." They did. Then he said, "Now find the rod that will just fill up that space." I don't know how the other children worked on the problem; I was watching the dark-haired boy. His movements were spasmodic, feverish. When he had picked a rod out of the pile in the center of the table, he could hardly stuff it in between his blue rods. After several trials, he and the others found that a light green (3) rod would fill the space.

Then Gattegno, holding his blue rods at the upper end, shook them, so that after a bit the dark green rod fell out. Then he turned the rods over, so that now there was a 6-cm space where the dark green rod had formerly been. He asked the class to do the same. They did. Then he asked them to find the rod that would fill that space. Did they pick out of the pile the dark green rod that had just come out of that space? Not one did. Instead, more trial and error. Eventually, they all found that the dark green rod was needed. Then Gattegno shook his rods so that the light green fell out, leaving the original empty 3-cm space, and turned them again so that the empty space was uppermost. Again he asked the children to fill the space, and again, by trial and error, they found the needed light green rod. As before, it took the dark-haired boy several trials to find the right rod. These trials seemed to be completely haphazard.

Hard as it may be to believe, Gattegno went through this cycle at least four or five times before anyone was able to pick the needed rod without hesitation and without trial and error. As I watched, I thought, "What must it be like to have so little idea of the way the world works, so little feeling for the regularity, the orderliness, the sensibleness of things?" It takes a greateffort of the imagination to push oneself back, back, back to the place where we knew as little as these children. It is not just a matter of not knowing this fact or that fact; it is a matter of living in a universe like the one lived in by very young children, a universe which is utterly whimsical and unpredictable, where nothing has anything to do with anything else--with this difference, that these children had come to feel, as most very young children do not, that this universe is an enemy.

Then, as I watched, the dark-haired boy saw! Something went "click" inside his head, and for the first time, his hand visibly shaking with excitement, he reached without trial and error for the right rod. He could hardly stuff it into the empty space. It worked! The tongue going round in the mouth, and the hand clawing away at the leg under the table doubled their pace. When the time came to turn the rods over and fill the other empty space, he was almost too excited to pick up the rod he wanted; but he got it in. "It fits! It fits!" he said, and held up the rods for all of us to see. Many of us were moved to tears, by his excitement and joy, and by our realization of the great leap of the mind he had just taken.

After a while, Gattegno did the same problem, this time using a crimson (4) and yellow (5) rod between the blue rods. This time the black-haired boy needed only one cycle to convince himself that these were the rods he needed. This time he was calmer, surer; he knew.

Kiedy pierwszy raz czytałem ten opis, to nie mogłem zrozumieć i wyobrazić sobie, jak to ćwiczenie wyglądało, jak te klocki były układane, co uczestnicy z nimi robili. W końcu długo czytając i pomagając sobie asystentem AI wyobraziłem to sobie - ciekawe czy poprawnie. Myślałem, że to tylko ja miałem z tym trudność, ale M. napisał do mnie, że on też tego nie widzi i prosi o rysunki. Więc oto mój opis z rysunkami, jak ja to sobie wyobrażam. Uwaga - kolory na moich rysunkach są inne niż w powyższym opisie, bo tak mi się narysowało.

Uczestnicy ćwiczenia mają do dyspozycji klocki prostopadłościenne o przekroju kwadratowym, wszystkie o tym samym przekroju, ale o różnej długości. Klocki są różnych kolorów - kolor informuje, jakiej długości jest klocek.

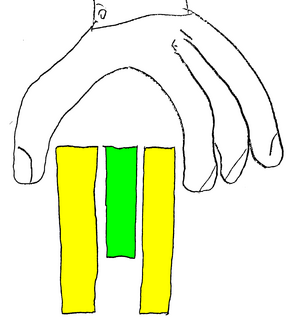

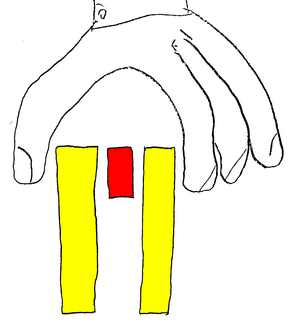

Ćwiczenie zaczyna się od tego, że uczestnicy ustawiają równolegle dwa klocki o długości 9 cm i wkładają między nie klocek o długości 6 cm:

Ich pierwsze zadanie to znaleźć, jaki klocek pasuje w to wolne miejsce. Szukają, szukają i w końcu znajdują, że jest to klocek o długości 3:

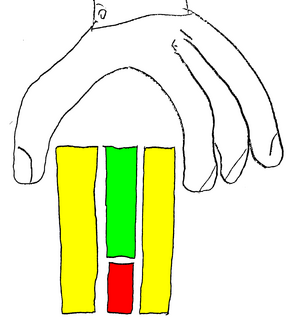

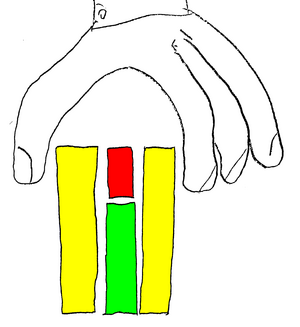

Wtedy uczestnicy łapią klocki z drugiej strony:

i wyrzucają klocek o długości 6:

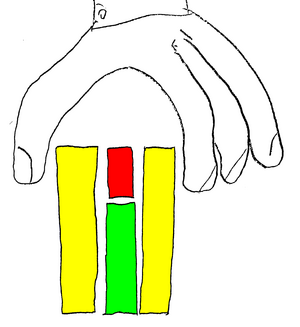

i z powrotem obracają klocki luką do góry:

Ich kolejne zadanie polega na tym, żeby teraz znaleźć klocek pasujący do tej luki.

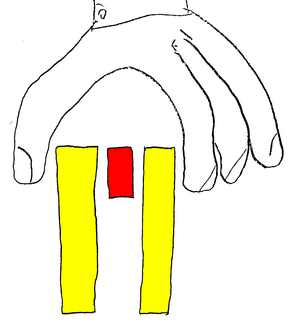

Normalny człowiek od razu widzi, że teraz potrzebny jest znowu klocek o długości 6:

Ale w tym ćwiczeniu uczestnicy byli bardzo nieinteligentni i zajęło im wiele prób, zanim odkryli, jak to działa.